이 기사는 해외 석학 기고글 플랫폼 '헤럴드 인사이트 컬렉션'에 게재된 기사입니다.

|

| 중국의 수도 베이징에서 한 시민이 이 나라 최대 부동산 개발업체이자 부동산발 위기의 진앙으로 지목된 비구이위안(碧桂園·컨트리가든)이 건설 중이던 주거용 건물 근처에 앉아 쉬고 있다. [로이터] |

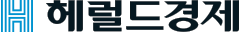

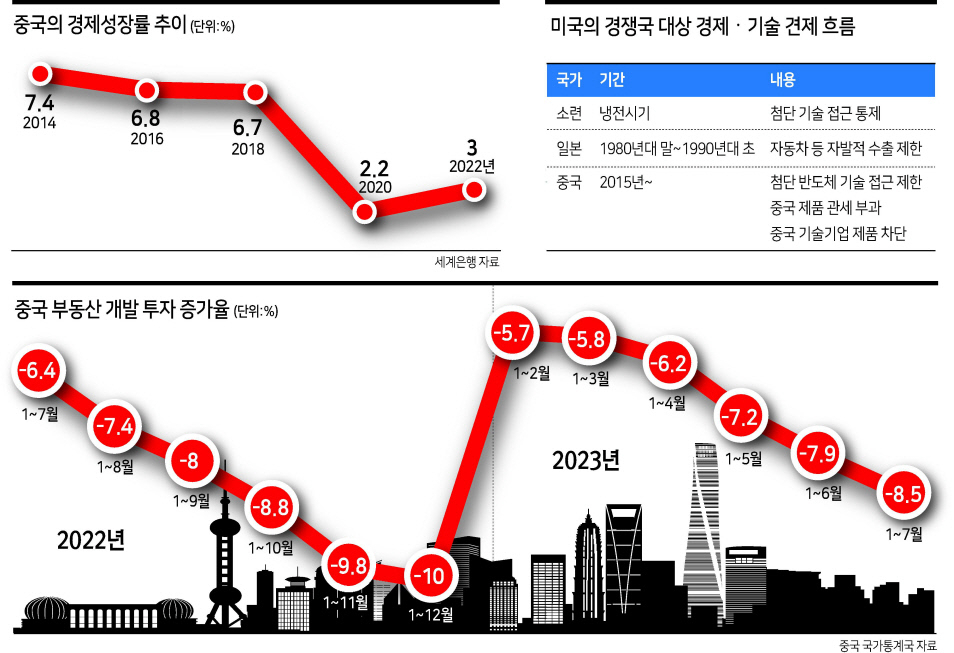

중국 경제가 둔화하고 있다. 현재 중국의 2023년 국내총생산(GDP) 성장률은 5% 미만으로 예측되고 있다. 지난해에 나왔던 예측치보다 낮아진 수치이며, 2010년대 후반까지 중국이 누리던 높은 성장률에 비해 많이 낮다. 서구의 언론은 중국 부동산시장발(發) 금융위기와 과도한 부채 등 소위 중국의 잘못에 대해 연신 보도한다. 하지만 이 둔화의 많은 부분은 중국의 성장을 늦추려는 미국의 조치로 인한 것이다. 미국의 반중(反中) 정책은 세계무역기구(WTO) 규정 위반이자 세계 번영에 대한 위협으로, 이러한 조치는 중단돼야 한다.

이번 반중 정책은 꽤 친숙한 미국 정책입안 매뉴얼에서 나온 것으로, 매뉴얼의 목표는 주요 경쟁국과 경제적·기술적 경쟁을 방지하는 것이다. 매뉴얼이 첫 번째로, 또 가장 노골적으로 적용된 사례는 냉전기간에 미국이 소련으로 유입되는 기술을 차단한 것이다. 미국은 소련을 적으로 선포했고 미국 정책은 첨단 기술에 대한 소련의 접근 차단을 목표로 했다.

이 매뉴얼이 두 번째로 적용된 사례는 덜 노골적이어서 사실상 식견이 있는 사람 대부분이 간과해왔다. 1980년대 말~1990대 초에 미국은 의도적으로 일본의 경제성장을 늦추려고 했다. 일본이 당시에, 또 지금도 미국의 동맹국이라는 점을 고려하면 놀라울 수 있다. 그러나 당시 일본은 ‘너무 성공하고’ 있었다. 일본 기업들은 반도체, 소비자가전, 자동차를 포함한 핵심 분야에서 미국 기업을 앞질렀고, 일본의 성공은 필자의 위대한 동료이자 하버드대학 교수였던 고(故) 에즈라 보겔(Ezra Vogel)의 저서 ‘Japan as Number One(재팬 애즈 넘버원)’을 포함한 많은 베스트셀러에서 주목받았다.

1980년대 중후반에 미국 정치인들은 (일본과 합의한 소위 ‘자발적’ 제한을 통해) 일본의 대미 수출을 제한하고 일본이 자국 통화를 과대평가하도록 압력을 가했다. 일본 엔화의 가치는 달러당 1985년 약 240엔에서 1988년 128엔, 또 1995년 달러당 94엔으로 상승하며 이로 인해 비싸진 일본 제품을 미국 시장에서 몰아냈다. 수출 증가세가 무너지며 일본은 부진에 빠졌다. 1980~1985년에 일본의 수출은 연간 7.9%씩 성장했지만 1985~1990년에는 수출 성장률이 연간 3.5%로 떨어졌고, 1990~1995년에는 연간 3.3%로 더 떨어졌다. 성장이 눈에 띄게 둔화하면서 많은 일본 기업이 자금난에 빠졌고, 이는 1990년대 초반 금융 붕괴로 이어졌다.

1990년대 중반에 필자는 일본에서 가장 힘 있는 정부 관료 중 한 명에게 ‘왜 일본은 성장을 재건하기 위해 화폐가치를 평가 절하하지 않는지’ 물은 적이 있는데 그는 ‘미국이 허용하지 않을 것’이라고 대답했다.

이제 미국은 중국을 겨냥하고 있다. 대략 2015년부터 미국의 정책입안자들은 중국을 무역파트너가 아니라 위협으로 간주하기 시작했다. 이런 관점의 변화는 중국의 경제적 성공 때문이었다. 중국이 2015년 로봇공학, IT, 재생에너지 및 기타 첨단 기술 분야에서 중국의 발전을 진흥하는 ‘중국제조 2025(Made in China 2025)’ 정책을 발표했을 때 중국의 경제적 성장은 미국의 전략가들에게 진지한 경종을 울리기 시작했다. 비슷한 시기에 중국은 주로 중국 금융, 기업, 기술을 통해 아시아, 아프리카 및 기타 지역 전역에 현대식 인프라 구축을 지원하는 ‘일대일로 정책’을 발표했다.

미국은 중국의 급속한 성장을 늦추기 위해 오래된 매뉴얼을 다시 꺼내 들었다. 버락 오바마 대통령은 먼저 중국을 제외한 아시아 국가들과 새로운 무역그룹을 만들 것을 제안했지만 도널드 트럼프 대선 후보는 더 나아가 중국에 대한 노골적인 보호주의를 약속했다. 반중 공약을 기반으로 2016년 대선에서 승리한 트럼프 대통령은 중국에 일방적인 관세를 부과했고, 이는 세계무역기구(WTO) 규정에 대한 명백한 위반이었다. WTO가 미국의 조치에 반대하는 판결을 내리지 못하도록 하기 위해 미국은 새로운 위원 임명을 차단해 WTO 상소기구를 무력화했다. 트럼프 행정부는 또한 ZTE와 화웨이 등 선도적인 중국 기술기업의 제품을 차단하고 동맹국에도 똑같이 하도록 촉구했다.

조 바이든 대통령이 취임했을 때 (필자를 포함한) 많은 이는 바이든이 트럼프의 반중 정책을 번복하거나 완화할 것으로 기대했다. 하지만 상황은 반대로 전개됐다.

바이든은 오히려 규제를 배가해 트럼프가 부과한 중국에 대한 관세를 유지했을 뿐 아니라 첨단 반도체 기술과 미국 투자에 대한 중국의 접근을 제한하는 새로운 행정명령에 서명했다. 미국 기업들은 비공식적으로 공급망을 중국에서 다른 국가로 옮기도록 권고받았고, 이 프로세스는 오프쇼어링(offshoring)과 대조돼 프렌드쇼어링(friend-shoring·우호국 혹은 동맹국과 공급망 구축)이라고 불린다. 이런 조치들을 시행함에 미국은 WTO의 원칙과 절차를 완전히 무시했다.

미국은 중국과 경제전쟁을 벌이고 있다는 사실을 강력히 부인하지만 옛말에 ‘오리처럼 생기고, 오리처럼 헤엄치고, 오리처럼 꽥꽥대면 오리일 것’이라고 했다. 미국은 익숙한 매뉴얼을 사용하고 있고, 워싱턴 정치인들은 중국을 반드시 억제하거나 패배시켜야 할 적으로 지칭하며 전시에 쓰일 만한 언사를 보이고 있다.

그 결과는 중국의 대미 수출 양상의 변화로 나타나고 있다. 트럼프가 2017년 1월 대통령에 취임했을 때 미국의 상품 수입 중에서 중국 제품은 22%를 차지했다. 2021년 1월 바이든이 취임했을 때 미국 수입에서 중국이 차지하는 비중은 19%였고, 2023년 6월 기준 미국의 중국 수입 비중은 13%로 급락했다. 2022년 6월과 2023년 6월 사이 미국의 대중 수입이 무려 29%나 감소한 것이다.

물론 중국 경제의 역학은 복잡하며, 미·중 무역만으로 결정되는 것은 아니다. 아마도 중국의 대미 수출은 부분적으로는 반등할 것이다. 그러나 바이든이 2024년 대선을 앞둔 상황에서 중국과의 무역장벽을 완화할 가능성은 작다.

미국에 안보를 의존하고 있어 미국의 요구를 따를 수밖에 없던 1990년대의 일본과 다르게 중국은 미국의 보호무역주의 앞에서 선택지가 더 넓다. 개인적으로 가장 중요한 점은 중국이 일대일로 정책의 확장 등과 같은 정책으로 아시아, 아프리카, 남미 등의 지역으로 수출을 상당히 늘릴 수 있다는 것으로 생각한다.

필자는 중국을 견제하려는 미국의 시도는 원칙적으로 잘못됐을 뿐 아니라 실제로도 실패할 운명이라고 평가한다. 중국은 세계 경제 속에서 다른 파트너를 찾아 자국의 무역을 확대하고 기술 발전을 지원할 것이다.

제프리 삭스 미국 컬럼비아대 교수

The US Economic War on China

Jeffrey D. Sachs

China‘s economy is slowing down. Current forecasts put China’s GDP growth in 2023 at less than 5%, below the forecasts made last year and far below the high growth rates that China enjoyed until the late 2010s. The Western press is filled with China‘s supposed misdeeds: a financial crisis in the real-estate market, a general overhang of debt, and other ills. Yet much of the slowdown is the result of US measures that aim to slow China’s growth. Such US policies violate World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and are a danger to global prosperity. They should be stopped.

The anti-China policies come out of a familiar playbook of US policy-making. The aim is to

prevent economic and technological competition from a major rival. The first and most obvious application of this playbook was the technology blockade that the US imposed on the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The Soviet Union was America‘s declared enemy and US policy aimed to block Soviet access to advanced technologies.

The second application of the playbook is less obvious, and in fact, is generally overlooked even by knowledgeable observers. At the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, the US deliberately sought to slow Japan‘s economic growth. This may seem surprising, as Japan was and is a US ally. Yet Japan was becoming “too successful,” as Japanese firms outcompeted US firms in key sectors, including semiconductors, consumer electronics, and automobiles. Japan’s success was widely hailed in bestsellers such as Japan as Number One by my late, great colleague, Harvard Professor Ezra Vogel.

In the mid-to-late 1980s, US politicians limited US markets to Japan‘s exports (via so-called

“voluntary” limits agreed with Japan), and pushed Japan to overvalue its currency. The

Japanese Yen appreciated from around 240 Yen per dollar in 1985 to 128 Yen per dollar in 1988 and 94 Yen to the dollar in 1995, pricing Japanese goods out of the US market. Japan went into a slump as export growth collapsed. Between 1980 and 1985, Japan‘s exports rose annually by 7.9 percent; between 1985 and 1990, export growth fell to 3.5 percent annually; and between 1990 and 1995, to 3.3 percent annually. As growth slowed markedly, many Japanese companies fell into financial distress, leading to a financial bust in the early 1990s. In the mid-1990s, I asked one of Japan’s most powerful government officials why Japan didn‘t devalue the currency to re-establish growth. His answer was that the US wouldn’t allow it.

Now the US is taking aim at China. Starting around 2015, US policy-makers came to view China as a threat rather than a trade partner. This change of view was due to China‘s economic success. China’s economic rise really began to alarm US strategists when China announced in 2015 a “Made in China 2025” policy to promote China‘s advancement to the cutting edge of robotics, information technology, renewable energy, and other advanced technologies. Around the same time, China announced its Belt and Road Initiative to help build modern infrastructure throughout Asia, Africa and other regions, largely using Chinese finance, companies, and technologies.

The US dusted off the old playbook to slow China‘s surging growth. President Barrack Obama first proposed to create a new trading group with Asian countries that would exclude China, but presidential candidate Donald Trump went further, promising outright protectionism against China. After winning the 2016 election on an anti-China platform, Trump imposed unilateral tariffs on China that clearly violated World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. To ensure that WTO would not rule against the US measures, the US disabled the WTO appellate court by blocking new appointments. The Trump Administration also blocked products from leading Chinese technologies companies such as ZTE and Huawei and urged US allies to do the same.

When President Joe Biden came to office, many (including me) expected Biden to reverse or ease Trump‘s anti-China policies. The opposite happened. Biden doubled down, not only maintaining Trump’s tariffs on China but also signing new executive orders to limit China‘s access to advanced semiconductor technologies and US investments. American firms were advised informally to shift their supply chains from China to other countries, a process labelled “friend-shoring” as opposed to offshoring. In carrying out these measures, the US completely ignored WTO principles and procedures.

The US strongly denies that it is in an economic war with China, but as the old adage goes, if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it‘s probably a duck. The US is using a familiar playbook, and the Washington politicians are invoking martial rhetoric, calling China an enemy that must be contained or defeated.

The results are seen in a reversal of China‘s exports to the US. In the month that Trump came into office, January 2017, China accounted for 22 percent of US merchandise imports. By the time that Biden came into office in January 2021, China’s share of US imports had dropped to 19 percent. As of June 2023, China‘s share of US imports had plummeted to 13 percent. Between June 2022 and June 2023, US imports from China fell by a whopping 29 percent.

Of course, the dynamics of China‘s economy are complex and hardly driven by China-US trade alone. Perhaps China’s exports to the US will partly rebound. Yet Biden seems unlikely to ease trade barriers with China in the lead-up to the 2024 election.

Unlike Japan in the 1990s, which was dependent on the US for its security, and so followed US demands, China has more room for maneuver in the face of US protectionism. Most importantly, I believe, China can substantially increase its exports to the rest of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, through policies such as expanding the Belt and Road Initiative. My assessment is that the US attempt to contain China is not only wrongheaded in principle, but destined to fail in practice. China will find partners throughout the world economy to support a continued expansion of trade and technological advance.